It is easiest to accept happiness when it is brought about through things that one can control, that one has achieved after much effort and reason. But the happiness I had reached with Chloe had not come as a result of any personal achievement or effort. It was simply the outcome of having, by a miracle of divine intervention, found a person whose company was more valuable to me than that of anyone else in the world. Such happiness was dangerous precisely because it was so lacking in self-sufficient permanence. Had I after months of steady labor produced a scientific formula that had rocked the world of molecular biology, I would have had no qualms about accepting the happiness that had ensued from such a discovery. The difficulty of accepting the happiness Chloe represented came from my absence in the causal process leading to it, and hence my lack of control over the happiness-inducing element in my life. It seemed to have been arranged by the gods, and was hence accompanied by all the primitive fear of divine retribution.

„All of man’s unhappiness comes from an inability to stay in his room alone,“ said Pascal, advocating a need for man to build up his own resources over and against a debilitating dependence on the social sphere. But how could this possibly be achieved in love? Proust tells the story of Mohammed II, who, sensing that he was falling in love with one of the wives in his harem, at once had her killed because he did not wish to live in spiritual bondage to another. Short of this approach, I had long ago given up hope of achieving self-sufficiency. I had gone out of my room, and begun to love another – thereby taking on the risk inseparable from basing one’s life around another human being.

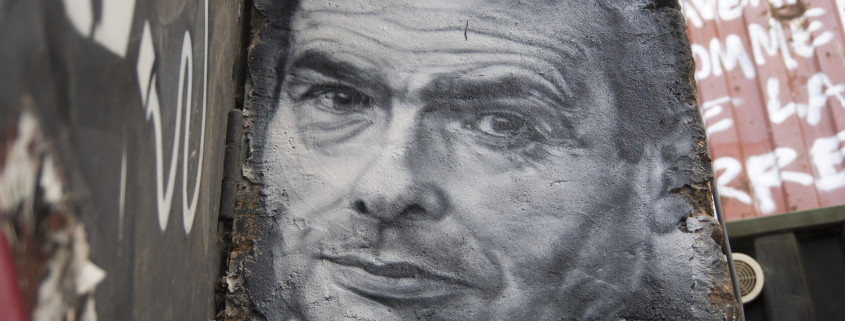

(Alain de Botton – On Love)

Mir geht’s so gut,

ich kann ja gar nichts sagen.

Mir geht’s so gut,

ich darf mich nicht beschwern.

Mir geht’s so gut,

manch andrer wäre froh.

Mir geht’s so schlecht,

weil’s mir so gut gehn muss.

(2010)

The difficulty of a declaration of love opens up quasi-philosophical concerns about language. (…) The words were the most ambiguous in the language, because the things they referred to so sorely lacked stable meaning. Certainly travelers had returned from the heart and tried to represent what they had seen, but love was in the end like a species of rare colored butterfly, often sighted, but never conclusively identified.

The thought was a lonely one: of the error one may find over a single word, an argument not for linguistic pedants but of desperate importance to lovers who need to make themselves understood. Chloe and I could both speak of being in love, and yet this love might mean significantly different things within each of us. We had often read the same books at night in the same bed, and later realized that they had touched us in different places: that they had been different books for each of us. Might the same divergence not occur over a single love-line?

She really was adorable (thought the lover, a most unreliable witness in such matters). But how could I tell her so in a way that would suggest the distinctive nature of my attraction? Words like „love“ or „devotion“ or „infatuation“ were exhausted by the weight of successive love stories, by the layers imposed on them through the uses of others. At the moment when I most wanted language to be original, personal, and completely private, I came up against the irrevocably public nature of emotional language.

There seemed to be no way to transport „love“ in the word L‑O‑V‑E, without at the same time throwing the most banal associations into the basket. The word was too rich in foreign history: everything from the Troubadours to Casablanca had cashed in on the letters. Was it not my duty to be the author of my feelings?

Then I noticed a small plate of complimentary marshmallows near Chloe’s elbow and it suddenly seemed clear that I didn’t love Chloe so much as marshmallow her. (…) Even more inexplicably, when I took Chloe’s hand and told her that I had something very important to tell her, that I marshmallowed her, she seemed to understand perfectly, answering that it was the sweetest thing anyone had ever told her.

(Alain de Botton – On Love)

When we look at someone (an angel) from a position of unrequited love and imagine the pleasures that being in heaven with them might bring us, we are prone to overlook a significant danger: how soon their attractions might pale if they began to love us back. We fall in love because we long to escape from ourselves with someone as ideal as we are corrupt. But what if such a being were one day to turn around and love us back? We can only be shocked. How could they be as divine as we had hoped when they have the bad taste to approve of someone like us? If in order to love we must believe that the beloved surpasses us in some way, does not a cruel paradox emerge when we witness this love returned? „If s/he really is so wonderful, how could s/he love someone like me?“

(Alain de Botton – On Love)

Viele Intellektuelle tun so, als würden sie glauben, oder glauben wirklich, daß ich gegen die Demokratie Position beziehe, wenn ich sage, die öffentliche Meinung existiert nicht, die Umfragen sind gefährlich. Weil, sagen sie, die Umfragen darin bestehen, die Leute zu beraten, und was gibt es demokratischeres? In Wirklichkeit sehen sie überhaupt nicht, daß die Umfrage kein Instrument demokratischer Beratung, sondern ein Instrument rationaler Demagogie ist. Die Demagogie besteht darin, die Triebe, die Erwartungen, die Leidenschaften sehr gut zu kennen, um sie zu manipulieren oder ganz einfach, um sie zu registrieren, sie zu bestätigen, was das Schlimmste sein kann (man denke nur an die Todesstrafe oder den Rassismus). Die Sozialwissenschaften werden oft als Herrschaftsinstrument benutzt.

(Pierre Bourdieu – Was anfangen mit der Soziologie?, in: Die verborgenen Mechanismen der Macht)

Neueste Kommentare